Transparency, clarity, and then trust key to easing encumbrance conflict

Regulatory initiatives aimed at preventing another financial crisis are helping fuel asset encumbrance, with more transparency – especially about non-covered bond sources of encumbrance – perhaps the best response in the absence of a silver bullet to resolving the conflict between unsecured and secured creditors, according to a panel featuring BaFin, EBA and ECB officials at a recent conference in Warsaw.

That asset encumbrance has increased over the past few years is largely undisputed by market participants – even if there are rare exceptions such as Germany – but beyond that there is little consensus, with the definition of asset encumbrance even seeming to come in for debate.

The complexity of the phenomenon was both illustrated by and addressed during a panel discussion at a Central European Covered Bond Conference organised by the Polish Mortgage Credit Foundation and the Association of German Pfandbrief Banks (vdp) in Warsaw on 22-23 November. Some 90 specialists from 12 countries took part in the event, which also tackled the implications for covered bonds of the EC bank resolution directive, residential mortgage funding structures in banking groups with centralised issuers, and the intricacies of transferring mortgages, or specifically “hypothecs” for covered bond funding purposes.

Michael Zlotnik, independent rating advisor, set the scene by highlighting the multiple sources of asset encumbrance, of which covered bonds are merely one alongside financial instruments such as repos and derivatives, and the various regulatory initiatives that are helping fuel it at the same time as regulatory responses to prevent the next financial crisis are being sought.

“There is no ‘silver bullet’ to resolve the conflict between unsecured and secured creditors to ensure equal treatment in the event of an insolvency,” he said. “It’s very political, and responses could have a severe impact on bank funding models and structures.”

The role of rating requirements in further fuelling asset encumbrance was also discussed. Christian Moor, policy advisor, securitisation and covered bonds at the European Banking Authority (EBA), but speaking in a personal capacity, said that he is worried about the influence of ratings in fuelling overcollateralisation levels and rating triggers on the freely available assets or collateral.

He noted that asset encumbrance is a “medium term” risk for the EBA, although it is “of course a concern as asset encumbrance levels have gone up”.

“There are still a few things to be clarified before a real discussion can start,” he said. “There is a difference between asset encumbrance in a going concern and a gone concern situation, and the definition of asset encumbrance and what is the best way to measure it are still not clear.”

Steffen Meusel, senior advisor at BaFin, the German financial supervisory authority – also speaking in a personal capacity – flagged how the inclusion of rating thresholds in regulatory frameworks can have an impact on asset encumbrance, and that this needs to be borne in mind.

“Regulators have to be very careful about the effects of their actions,” he said. “For example, in Solvency II the extension of privileged treatment to double-A rated covered bonds is important, because it reduces pressure to go for a triple-A rating and therefore overcollateralisation and asset encumbrance.

“The foregoing notwithstanding, the provisions of the German Pfandbrief Act ensure the Pfandbrief’s high standard of safety.”

Covered bond analysts regularly point out that there is an important flipside to the asset-encumbering, loss-given-default-increasing effects of covered bonds, namely that they reduce the probability of default, and according to Pontus Åberg, senior economist at the European Central Bank, the positive effects of the ECB’s operations as a collateral taker also need to be borne in mind.

He said that the ECB contributes to asset encumbrance in its role as collateral taker, and that its longer term refinancing operations (LTROs) were criticised for this, but that it is important to recognise the broader context in which the operations were carried out.

“The two LTROs helped reduce tensions by improving bank liquidity and funding profiles,” he said, “which enabled access to market funding.

“Contrary to the argument that we contributed to asset encumbrance, the ECB’s actions helped open up the senior unsecured market and increase counterparty trust. So yes, we encumber assets but you have to take into account the effects.”

Transparency: not all good

Greater transparency was identified by several panellists as a sensible means of responding to heightened levels of asset encumbrance and the uncertainty that this causes, although there were different views on just how far this should go.

Hans-Dieter Kemler, member of the management board at BRE Bank in Warsaw, said that transparency, especially of non-covered bond based asset encumbrance, is important, and that this requires discipline by banks, and trust from investors.

“The trend to higher asset encumbrance is an expression of a lack of trust,” he said. “In the past there was more of a choice involved between secured and unsecured debt, with decisions in part based on arbitrage.

“It is important that banks retain the ability to issue unsecured debt as it is a necessary and complementary financing tool, even in the context of covered bond issuance to cover the overcollateralisation requirements as well as higher than cover pool eligible loan-to-value exposures.”

Åberg at the ECB supported greater transparency as a means of dealing with higher asset encumbrance levels, and said that it would be best if this was market-led.

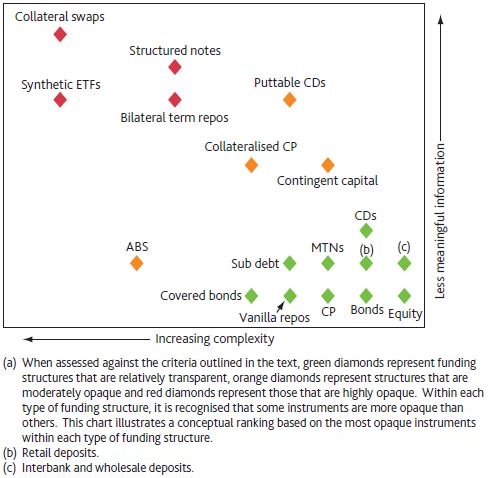

A chart displayed by Zlotnik (see below) showed how transparency generally declines the more complex a funding structure is, with covered bonds among the relatively transparent structures, and BaFin’s Meusel said that in covered bonds the asset-encumbering effect is generally known.

Other sources of asset encumbrance, however, such as derivatives and the ECB’s LTROs, are much less transparent, he noted. He said that he agreed with calls for detailed transparency made recently by a Financial Stability Board disclosure taskforce, but warned that too much disclosure can also have unintended consequences.

“Regulators have to be careful,” he said, “because there can be self-fulfilling liquidity problems if there is too much transparency. There should be full transparency for regulators, and improved transparency for the market, but there needs to be a gap.”

The conflict between secured and unsecured creditors can be reduced if pricing accurately reflects the risks, added Meusel, but this requires transparency.

“Pricing has to show risk in the correct way,” he said. “And if the price is right you will also have unsecured investors.”

Not everyone was impressed with calls for greater transparency, however, with a bank chief financial officer in the audience warning against information overload.

“We have too much disclosure,” he said, “and people can’t appreciate all the information.”

And while the panellists spoke about the need for clarity of regulation, he added, the opposite is happening.

“The bail-in prospect is a source of unrest,” he said.

To which a panellist responded: “I agree, but don’t forget the politicians started the regulations.”

Complexity and information availability for funding structures

Source: Bank of England, Michael Zlotnik